The Risk of a Lost Decade for Stocks

Stock risk is most associated with short-term volatility like in March 2020. This post examines the frequency of long-term periods of low returns.

Everybody wants to know…

This is the wrong question for a long-term investor. Who cares if markets bottom in March or May? My main concern is that U.S. stocks could go nowhere for a decade.

Stock risk is often associated with short-term volatility like we saw in March. True risk is an extended period of zero returns. Retirees with high withdrawal rates run out of money and young investors get jaded on stocks for the rest of their lives. This post explains why a lost decade could happen and how it would impact your portfolio.

The Historical Base Case

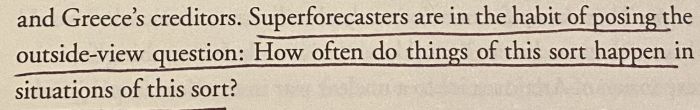

Superforecasting talks about the importance of knowing the historical base case:

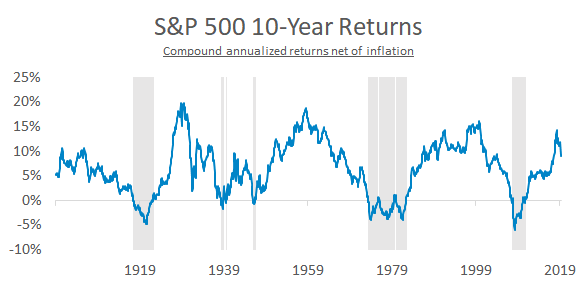

I think the average investor has an overly optimistic base case for how stocks perform over 10-year horizons. The S&P 500 has spent one-tenth of the time since 1900 with a negative inflation-adjusted return over the prior decade.

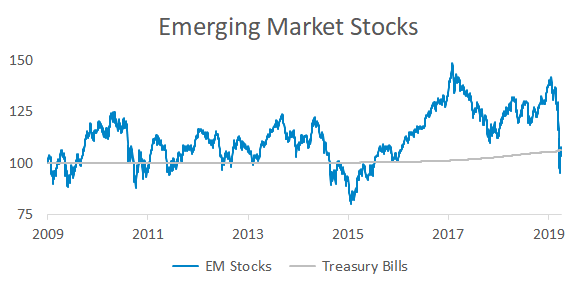

Lost decades aren’t just a historical artifact. International investors in 2020 know exactly what they feel like:

Emerging market stocks have compounded at 0.4% per year since 2010 with three 20% drawdowns. That’s a ton of volatility to underperform risk-free Treasury bills.

The historical base case of a lost decade should anchor future expectations. Here’s what young investors and retirees can do to protect themselves:

Example #1: Young Investor

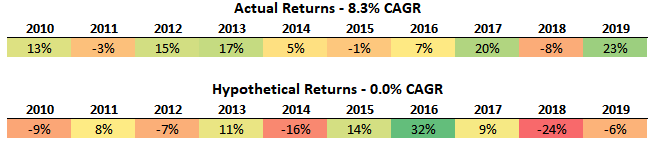

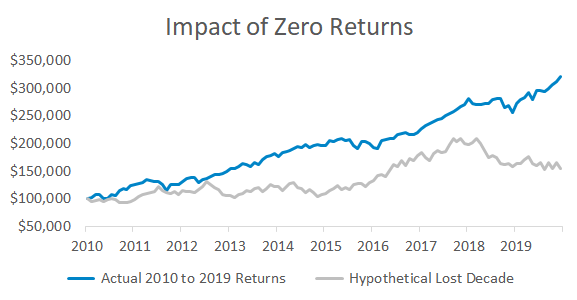

Consider two 30-year old investors. Both start with $100k, save $500 per month, and invest in a portfolio of 80% in global stocks and 20% in 10-year Treasuries. The only difference is their return path.

One experienced the actual returns for this portfolio since 2010. The other followed a hypothetical path that ultimately earned 0%:

No surprises here. Lower returns = less money.

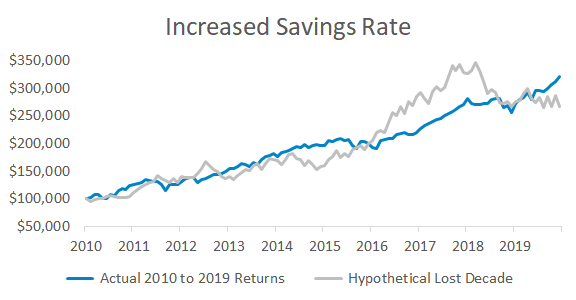

But as Nick Maggiulli has written about, your savings rate is more important than your returns. What if the hypothetical 2020 investor boosted their monthly savings to $1500?

The easier way to save an extra $1000 is to make more money, not cut expenses. That’s why the solution to a lost decade for a young investor lies outside of their portfolio. Learning a new skill is a more powerful financial lever than tinkering with your portfolio to boost returns.

If someone asks “I want to start something on the side, where do I begin?” I always point them to Ramit Sethi’s GrowthLab. That’s not an affiliate link – one of his courses really helped me years ago and he’s now made the core content free.

Example #2: Retired Investor

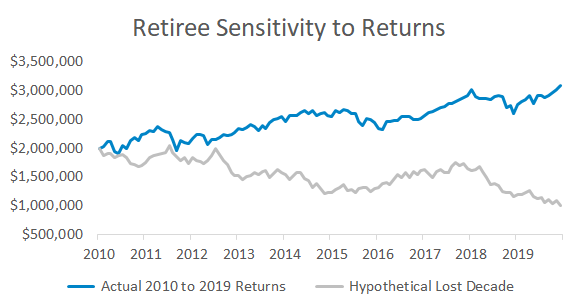

Take two retirees with $2 million, $100k in annual withdrawals, and portfolios in a 50/50 mix of global stocks and 10-year Treasuries. Using the same actual and hypothetical return paths from above, here’s how each retiree performed:

Returns in early retirement can mean the difference between leaving a substantial legacy or running out of money. That’s called sequence risk, and sequence risk is amplified as portfolio withdrawals increase.

Three ways to reduce sequence risk include dynamic portfolio withdrawals, cash buffers, and investment strategies that reduce drawdowns. Here’s a walkthrough of all three.

Some experienced the March volatility and are now thinking about selling everything. Others missed the rip and want to know if it’s time to get back in. Kneejerk investing decisions are not a way to win this game over the long-term. There’s a huge mismatch between the ease of investing and the impact of those actions. Imagine how carefully you would make decisions if you measured how they would affect your family over the next 100 years.

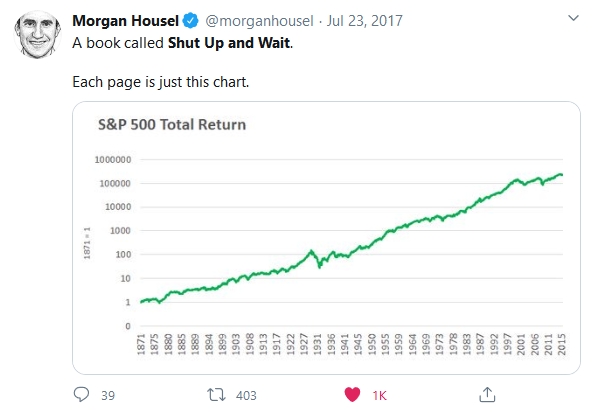

Even though stocks can experience a lost decade, that doesn’t mean you should go to all cash. Portfolio construction is about taking smart risks and matching investments to your time horizon. It’s possible to both mentally prepare for low returns in the short-term and know that stock investors are massively rewarded over the long-term:

Summary

- U.S. stocks have spent one-tenth of the time since 1900 with negative 10-year returns after inflation.

- Young investors should increase their savings rate and retirees should reduce sequence risk.

- Avoid making a kneejerk portfolio decision if we experience additional downside this year.