What Backtests Hide

Investors crave certainty about future returns and backtests seem to provide that. Here's what they don't show.

Investors crave certainty about future returns and historical backtests seem to provide that. This post shows some of their limitations and two strategies that haven’t measured up to past performance.

Backtests distort our perception of what’s truly long term. Modern market history starts in the early 1900s. Putting Time In Perspective shows how short of a period that actually is. Everything we know about financial markets is in the light blue rectangle:

We laugh at investing approaches used 100 years ago…

…and 100 years from now I’m sure people will laugh at some of today’s “evidence-based” strategies too.

But another century of data doesn’t guarantee future investors will be smarter. Financial markets aren’t a field where we can brute force our way to success with data and hard work. In 1969 we put a man on the moon. In 2020 we have much more information and computing power – but still have no clue where the S&P will close next week.

Another issue with backtests is that they can’t capture how popularity impacts performance:

Capital is rewarded when it’s scarce and competition is low. In 1962 Buffett had $7 million to invest in cheap, overlooked companies. In 2020 there’s $980 billion in value mutual funds and $200 billion in value ETFs. It’s reasonable to assume performance degrades as competition increases and more people chase the same type of investment.

Here are two recent examples where backtests disappointed:

Value Investing

Value strategies tell a compelling story and appeal to the part of us that loves a good sale. The approach was a niche strategy in the 1950s, academics then wrote papers with terrific backtests, and eventually managers raised billions from hopeful investors.

The popularity shifted value away from its contrarian roots:

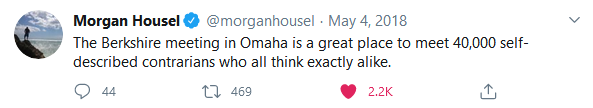

It’s probably not a coincidence traditional value approaches started underperforming after the seminal Fama-French paper was published:

Most value funds are still based on the price-to-book ratio. While informative for old economy stocks, it’s much less useful for tech companies and share repurchasers.

“Value investing is dead” is too extreme of a claim. But I wouldn’t hold out hope for the group of strategies that continue to define a company’s value with last century’s definition.

Trend Following

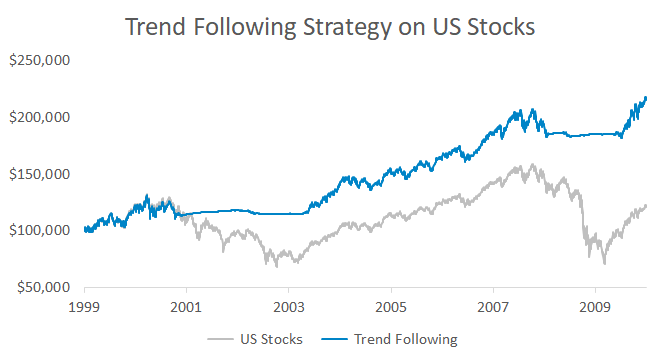

Portfolio hedging was massively in demand after 2008. Some investors turned to trend following, an approach that owns stocks when they’re going up and sells out when they’re going down. Who wouldn’t love this backtest?

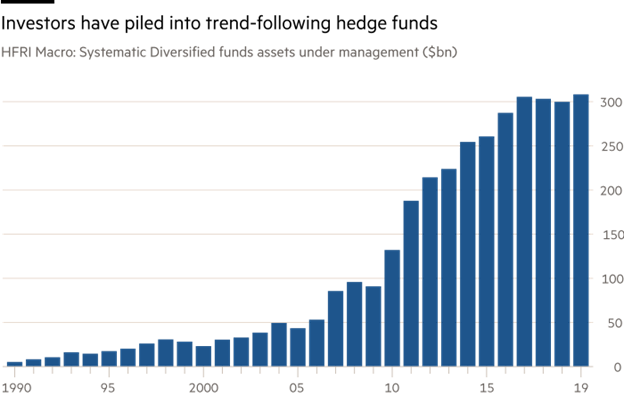

Money poured into trend following and its related strategies:

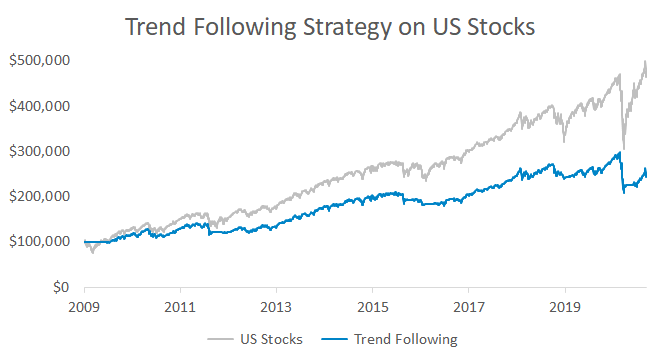

Recent performance has been lackluster:

The main problem with trend strategies is that they’re vulnerable to the speed of a market crash. They work well in slower downturns like 2008, but aren’t fast enough to protect in quick drops like October 1987. This doesn’t mean trend following is broken, but it does mean the strategy can’t always reduce risk like some marketed it after 2008.

Ed Seykota said “everybody gets what they want out of the market.” Regardless of performance, some strategies will always deliver an emotional payoff. What sounds smarter:

- “I’m in a hedge fund that uses proprietary models to observe 14 million data points per day. They charge 2%, but their backtested alpha has made up for that.”

- “I pay Vanguard 0.03% for an index fund because I have no idea which stocks will do best.”

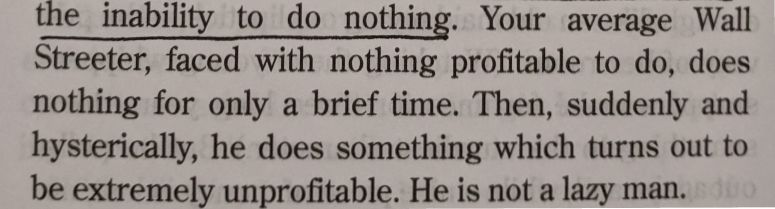

People go to Las Vegas and pay money to feel excited. Markets are similar. Complex strategies meet the constant investor desire to do something, regardless of if the activity adds value.

Adaptation vs. Perseverance

How can you tell if a strategy’s best days are in the past? I don’t know. But I do know it’s tricky from a manager’s perspective if they need to make a change.

The biggest career risk for a professional investor is being boxed into one type of strategy. Hugh Hendry ran a hedge fund that did great in 2008 and he developed a reputation for being pessimistic. In 2013 he changed his mind and became more bullish on risky assets. History proved him right but Hendry wasn’t rewarded:

He no longer fit the mold for what his investors wanted, even though a stubborn one-track manager isn’t what they needed.

I respect Hugh because his public reversal was so rare. When confronted with evidence that they’re wrong, most managers get defensive rather than question their assumptions.

Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof. - John Kenneth Galbraith

For years I managed a strategy focused on downside protection. This spring I finished a research project on a simpler way to achieve that.

I had two choices:

Option #1 would have been easy in the short term. Option #2 is what I chose, even though it was tough to say to clients “That strategy I ran for years? There’s a simpler way to do the same thing.” The next few posts will cover what I found.

Summary

- What we label as long-term market relationships are still relatively new.

- Strategy popularity can impact performance.

- Complex strategies sound smart because doing anything feels better than sitting still.