Value Averaging: An Alternative to DCA or Lump Sum

This post explores what value averaging is, how it works, and how to implement the strategy.

Michael Edleson wrote Value Averaging: The Safe and Easy Strategy for Higher Investment Returns in 1991. The publisher soon went out of business and prices for used copies rose – similar to what’s happened with Seth Klarman’s Margin of Safety. The book is now back in print and this post explains how value averaging works and why I use it instead of dollar cost averaging.

Dollar cost averaging (DCA) invests the same amount of money each period, regardless of price. DCA is a systematic way to lower your cost basis since it buys more shares when prices are lower.

“Dollar cost averaging gives you time diversification.“John Markese

Value averaging targets a specific portfolio value each period. By focusing on value rather than cost, investment amounts vary based on recent portfolio performance. Value averaging avoids big allocations to markets that race higher and panic selling as markets drop.

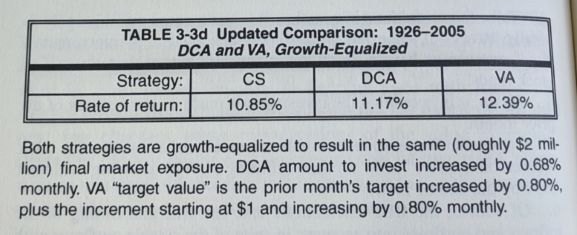

Edleson found that value averaging outperformed DCA and CS (constant share) strategies as applied to US stocks from 1926 to 2005.

Value Averaging Examples

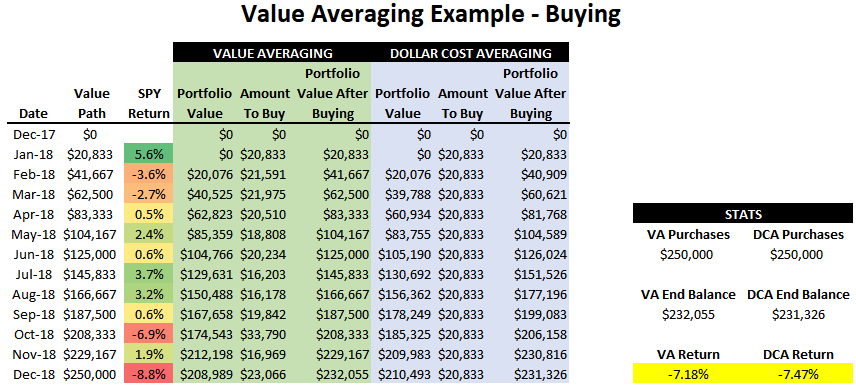

Let’s say you wanted to allocate $250,000 to the S&P 500 during 2018.

A DCA plan would call for purchasing $20,833 per month. Here’s how value averaging worked:

The value averaging approach outperformed DCA by 0.29% since it reduced purchases after strong Q2 performance and increased purchases as the market fell in Q4.

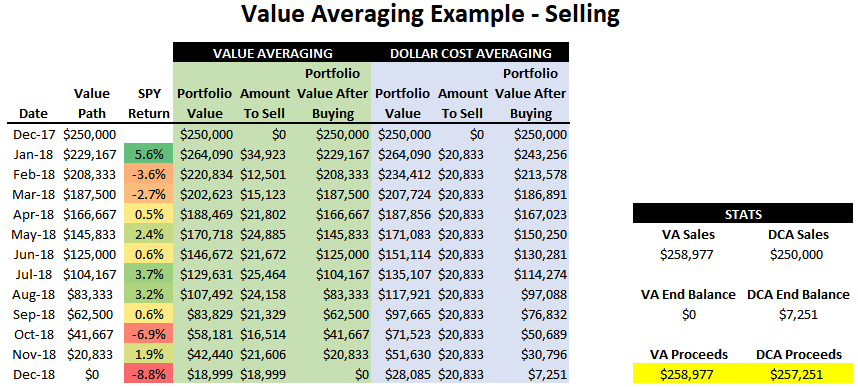

Value averaging is equally effective when withdrawing from a portfolio.

Let’s say you wanted to liquidate $250,000 invested in the S&P 500 during 2018:

Value averaging resulted in an additional $1,725 of withdrawals.

Value Averaging Implementation Details

- Value averaging cannot turn a bad year into a good year. The strategy itself is far more important than the allocation rules you use.

- I use a modified version of value averaging where the value path increases by a fixed amount. The original version adjusts the value path by a growth factor. This is because ten years into value averaging the monthly performance will often make up for the entire value path change. There’s little difference between a fixed and variable value path for time horizons of less than a few years.

- Value averaging can call for a huge amount of purchases after severely negative performance. You might want to introduce max thresholds so you can actually stick with the strategy and won’t second guess the value averaging output. When allocating a fixed amount of new capital, I set a ceiling so that value averaging never calls for allocating more cash than there is available.

- DCA, value averaging, and portfolio rebalancing are mean-reverting frameworks. Value averaging adds the most value in volatile and mean-reverting markets. Using value averaging during the trending late 1990s would have consistently allocated less money than DCA. This could have been good or bad depending on your time horizon.

My Spreadsheet

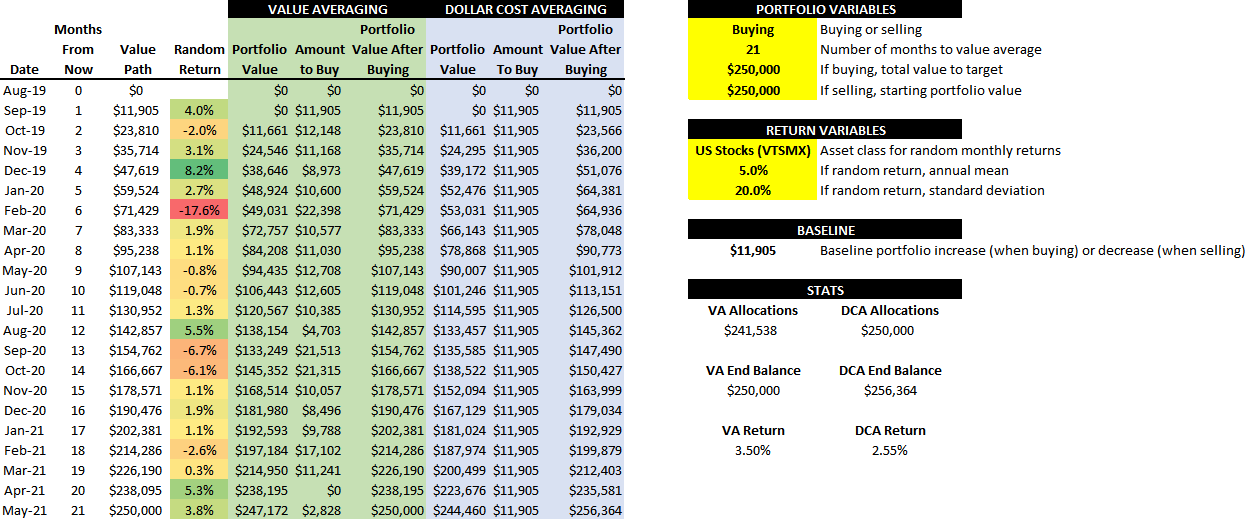

Here’s a Google Sheets link to the value averaging spreadsheet I use.

Download an Excel copy to modify the highlighted parameters. You can select if you’re buying or selling, your time horizon, and how much you want to buy or sell. The return column pulls a random series of returns for your selected asset. Entering a new value anywhere in the sheet refreshes the return column.

In practice this return column would be filled in with the actual performance of what you’re investing in.

Summary

Value averaging is a powerful alternative to dollar cost averaging. It’s a systematic way of ramping up allocations after negative performance and reducing allocations after strong performance. Especially in today’s richly valued market, a value averaging strategy can enforce discipline to take advantage of lower prices if they materialize.