Investment Switch Calculator

Sometimes it’s worth paying tax on an embedded gain to capture higher returns with a lower cost fund.

Measuring the benefit of switching to a lower-cost fund is a common question from investors with taxable accounts. This post links to my calculator and shows how to use it with two real-world examples.

There are five questions to ask when evaluating a fund replacement.

1. How will the gain in the current fund be taxed?

First check to see if it’s a short-term or long-term capital gain. Then determine the relevant tax rate with these tables.

2. What is the cost basis of the current fund?

Most brokers will show this, but here’s a worksheet if you have to manually calculate it.

3. How long do I plan to hold the investment?

Savings depend on your time horizon. In general, if you plan to liquidate something in the next few years it’s rarely worth a switch.

4. What are distributions like for each fund?

Distributions create a tax drag that needs to be factored in, so find current dividend yields from a site like Morningstar. If the current fund is a mutual fund then find capital gain distribution info from the issuer’s website. You’ll also want to get data on the percentage of qualified dividends for the current and replacement funds. For example, here’s Vanguard’s 2018 qualified dividend info.

5. How does my state tax capital gains?

Most treat them as ordinary income. Nine states don’t tax them at all and some others have unique rules for capital gains.

If you don’t need examples and just want the calculator, here’s an Excel download and an online Google Sheets version.

Example 1: Retired Investor in Active Mutual Fund

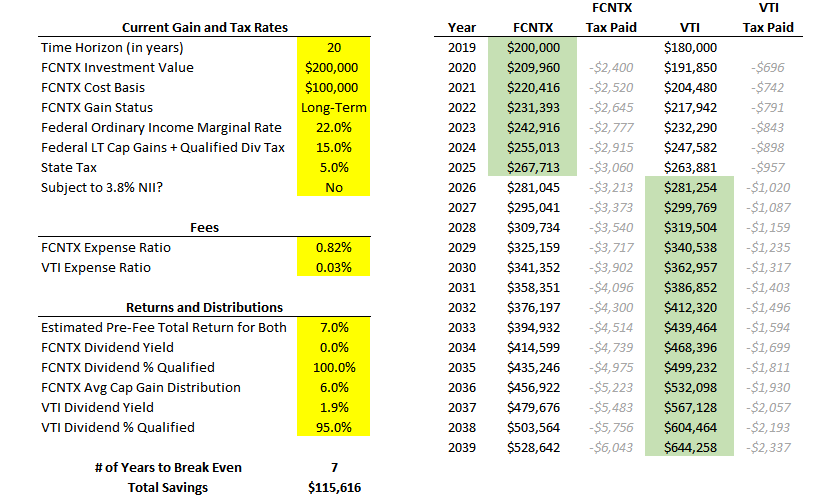

John recently retired and has a $100,000 long-term capital gain in Fidelity’s Contrafund (FCNTX). He wants to replace it with Vanguard’s passive total market U.S. stock fund (VTI).

On the existing gain he would owe 15% in federal and 5% in state taxes, for $20,000 total. FCNTX’s expense ratio is 0.82% and VTI’s is 0.03%. The question is: how long would it take for the lower cost of VTI to make up for the $20,000 tax hit?

Only looking at expense ratios hides the true cost of owning active mutual funds like FCNTX. Mutual funds have to distribute capital gains and switching calculations should account for this.

Annual capital gain distributions have averaged 6% for FCNTX, or $12,000 for a $200,000 investment. Since John pays a combined federal and state tax rate of 20% on long-term capital gains, this creates $2,400 in tax. Dividends also create a tax drag, but FCNTX hasn’t paid a meaningful dividend in years. VTI does pay a regular dividend and its yield is noted below.

Here’s how the calculator looks for this example. The FCNTX and VTI columns show the after-tax value of investments in each fund. Tax data is shown to visualize the annual tax drag.

It would take seven years for a switch to VTI to break even.

Example 2: Young Investor in Passive ETF

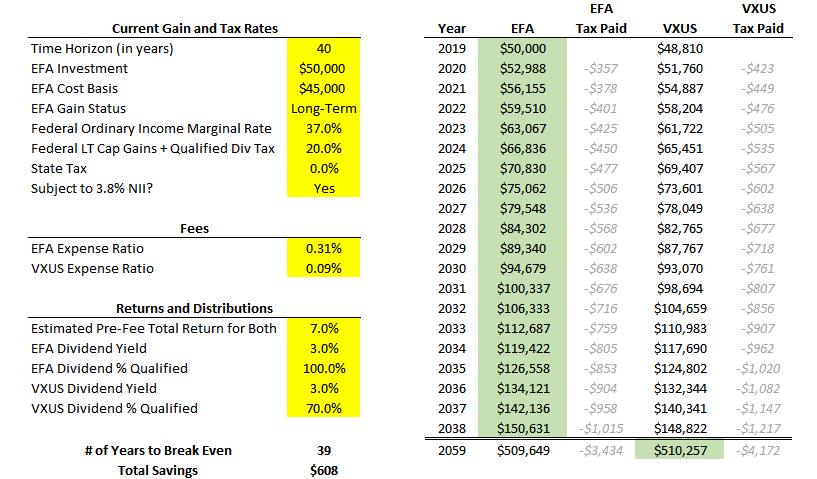

Stephen recently invested $45,000 into EFA, an international stock fund. He noticed that VXUS provides similar exposure at a lower expense ratio of 0.09% compared to EFA’s 0.31%.

Stephen pays 20% in long-term capital gains, lives in a state with no income tax, and has to pay the 3.8% net investment income tax. This analysis is simpler since neither fund pays capital gain distributions.

Here’s how the calculator looks with the above inputs. The line break hides a few decades to save space:

It would take thirty-nine years for a switch to VXUS to break even.

In this example it makes sense to stick with the EFA position, not reinvest dividends, and funnel new international exposure into VXUS. Without the tax hit on new purchases, VXUS’s lower fee makes up for its lower percentage of qualified dividends.

There’s nuance to each situation and the above info is not tax advice. The calculator is meant to get you most of the way to making an informed decision, but ultimately your advisor or CPA can provide the best input.

The calculator makes two assumptions that might not fit your scenario:

1. The same pre-fee return is assumed for both funds.

For example, both FCNTX and VTI were assumed to grow at 7% per year before fees. After FCNTX’s fee of 0.82% its net total return was 6.18%. After VTI’s fee of 0.03% its net total return was 6.97%. I made this assumption because most switching decisions I see compare a closet indexing high-fee mutual fund to an indexed low-fee ETF. In this event I think it’s fair to assume the same gross return. You’d want to use separate return assumptions if you had a high level of conviction that one of the funds would outperform over time.

2. Positions are not allocated to or withdrawn from.

Jake pointed out it’s important to remember that with mutual funds your capital gains are more spread out over time and with ETFs they’re deferred until you sell. This is relevant for investors who plan to withdraw from taxable positions. Also, the calculator assumes all capital gain distributions are taxed at the long-term rate. This is the most common outcome, but double check your fund issuer’s website for the exact split between long-term and short-term gains.

Summary

- It’s sometimes worth paying tax on an embedded gain to capture higher returns with a lower cost fund.

- A lower fee fund isn’t always better and you should measure the total impact before switching.

- Switch decisions need to factor in unique circumstances like your cost basis, time horizon, and state taxes.