Book Summary of The Four Pillars of Investing

William Bernstein’s The Four Pillars of Investing is one of my favorite books and covers the theory, history, psychology, and business of investing.

Here are my main takeaways of William Bernstein’s The Four Pillars of Investing:

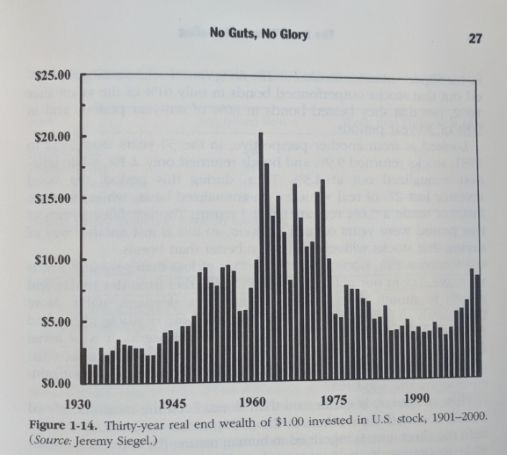

When you’re born has a huge impact on lifetime investment returns. Genetics play a role in our health and when we’re born has a big effect on our portfolio. An investor born in 1902 that invested 100% in U.S. stocks from 1932 to 1962 earned 10.2% per year – turning $100,000 into an inflation-adjusted $1.8 million.

Shifting the investment window to 1965 to 1995 results in only earning $343,000. We can’t control when we’re born so it’s important to focus on what we can control: saving more money, reducing fees, and increasing diversification.

Newsletter writers make money off of you, not for you. David Dreman tracked the opinions of market strategists back to 1929 and found that they were wrong 77% of the time.

Value Line is a popular research service. They offer 20+ publications with annual prices ranging from $149 to $1195. They also run an ETF that owns their top 100 stock ideas. The ETF has underperformed the broad US stock market by a cumulative 170% since 2004. If they can’t beat the market with their own research, who can?

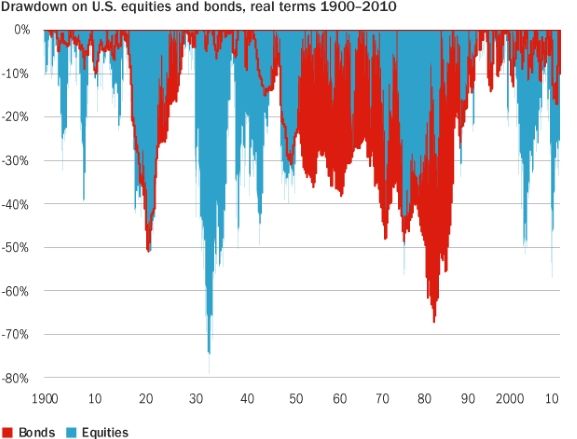

Inflation during the 20th century was a thousand-year flood for bond investors. Persistent inflation did not exist when major economies were on the gold standard. Investors were confident that present day dollars would maintain their purchasing power. Countries abandoned the gold standard after WW1 and bond investors realized that future interest and principal payments were worth significantly less.

The last century is an example that bonds in the long term are just as risky as stocks.

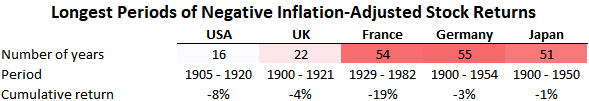

Stocks can go nowhere for decades. Some investors equate stock risk with severe but short crashes. The bigger risk is that stocks provide zero return over a multi-year stretch. For example, risk-free Treasury bills outperformed U.S. stocks from 1966 to 1982.

A knowledge of investing history will help keep you sane when everyone has lost their mind. There are two interesting episodes that stood out to me:

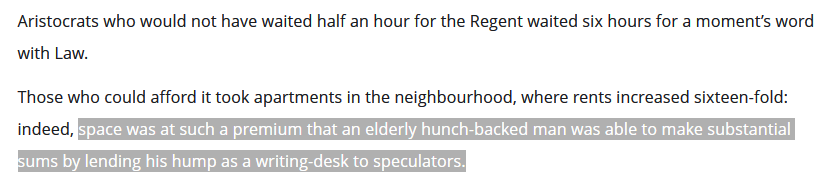

- The Mississippi Bubble: France was in a ton of debt in the early 1700s and looked to John Law for help. Law formed a central bank to issue paper money backed by gold – an innovation in the era of metallic money. Law then created the Mississippi Company to exploit resources in the Louisiana Territory. France viewed the issuance of Mississippi stock as a way to extinguish their debt. The bubble collapsed when investors realized there wasn’t enough gold to back all of the newly created paper money.

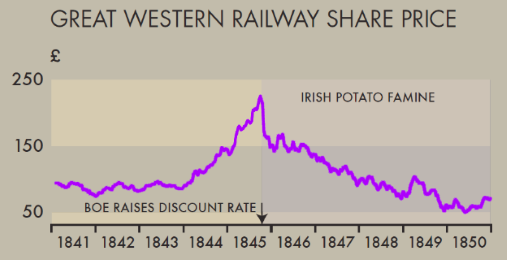

- Railway Mania: Railroads made overland travel safe, cheap, and fast. Queen Victoria’s first railway trip in 1842 was the main catalyst for the public interest in railroad shares. Thousands of miles of new railway track was created – some literally going nowhere. Railroad companies floated shares to an eager public. Higher interest rates stopped the bubble in 1845.

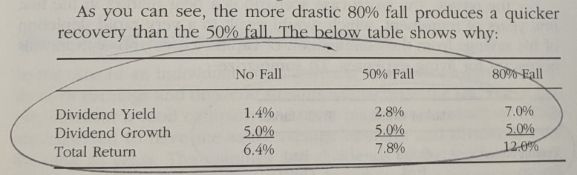

Young savers should pray for a stock market crash. The most sustainable way to get high returns is through a dramatic fall in prices. Dividend reinvestment at lower prices more than makes up for the initial drop. This is only true over multi-decade time horizons, retirees are more sensitive to short-term returns and should hope for a sustained rise.

Most of the investment industry fills their time with nonproductive work. The average person can buy an index fund and outperform the majority of professional stock pickers. The average person cannot scrub into an operating room and remove an appendix.

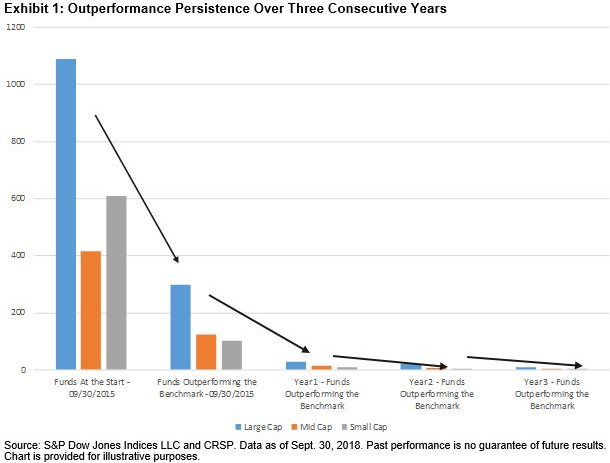

Investing is not a traditional skill because hard work does not necessarily translate to an increase in returns. If this was the case there would be persistence in manager performance, with good stock pickers steadily outperforming. Research shows the opposite is true.

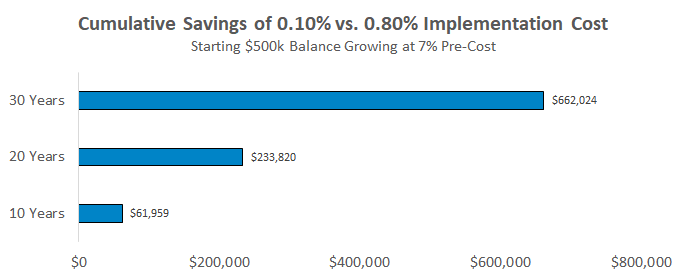

You have to know your implementation cost. It’s easy to know a manager’s fee. But do you know the cost to implement their strategy? This cost is a combination of expense ratios and transaction costs. Consider two investors. One pursues a strategy that uses funds with expense ratios of 0.50% and generates 0.30% in trading costs. Their implementation cost is 0.80% per year.

Compare that to an investor who uses a strategy with a lower implementation cost of 0.10%. If both investors start with $500,000 and compound at 7% gross per year, the investor with the lower implementation cost saved $662,024 over three decades.

Avoid three of the most common investor biases. Like exercise, overcoming a behavioral bias is simple but not easy. Knowledge of a bias doesn’t mean you won’t make it, but awareness is a step in the right direction.

- Needing entertainment: People routinely exchange large amounts of money for excitement. Research shows that investors gravitate toward lottery-style investments like penny stocks and options. Making 50% on a trade might be a good story for your friends, but investors who worked hard for their savings and shouldn’t treat them like a gamble.

- Focusing on the wrong risk: Don’t judge a long-term plan by short-term performance. Risk is not a 20% drop in stocks. True risk is the possibility that you constantly hop between strategies, never stick to a plan, and retire with little to show for decades of saving.

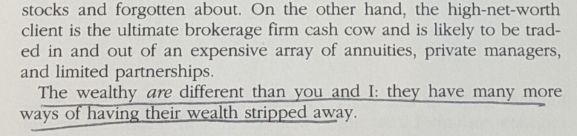

- Country club syndrome: Wealthy people pay for nice things like private schools and exclusive clubs. Should they also invest differently? Bernstein said, “wealthy investors need to realize they’re the cash cows of the investment industry and are regularly fleeced.” Most hedge funds and private equity partnerships have monster fees yet have earned lower returns than regular stocks and bonds.

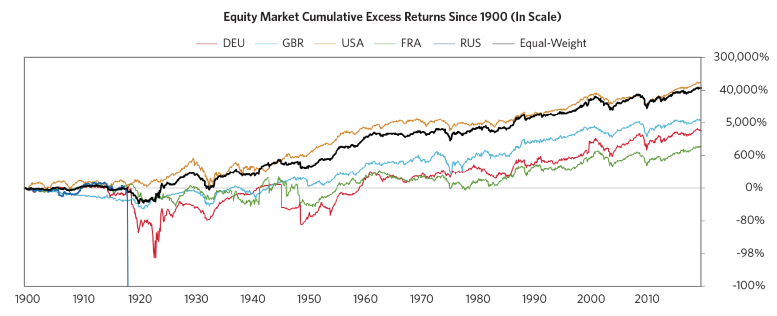

U.S. stock returns over the past 200 years are a best case scenario. The U.S. was an emerging market in the 1800s – not the powerhouse it is today. A more realistic return estimate accounts for other countries over a long period of time. A globally diversified approach (black line below) avoids the concentration risk of investing in a single country.

The Four Pillars of Investing is one of my favorite books on investing and I highly recommend it.