Book Summary of Taleb’s Antifragile

The opposite of fragility isn’t robustness, but antifragility. This post summarizes one of my all-time favorite investing books.

Nassim Taleb is a polarizing guy. He gets in Twitter fights, eats a lot of squid ink pasta, but also has many fans. I enjoy his writing and, among all his books, think Antifragile is the most complete description of his philosophy on life and markets. Here are my main takeaways:

- The opposite of fragility isn’t robustness, but antifragility. Fragile things (fine china, portfolios only invested in a single position, a “why me” mentality) easily break. Robust things (a piece of metal, broadly diversified portfolios, stoicism) endure change. Antifragile things (options, a “failure leads to growth” mentality) benefit from volatility and change. Fragility implies you’ve got more to lose than to gain. Antifragility implies you’ve got more to gain than to lose.

- Suppressing randomness and volatility weakens complex systems. Park rangers light small fires to prevent flammable material from building up in a forest. Hidden vulnerabilities tend to accumulate at corporations after long periods without setbacks. A lack of market volatility also tends to encourage excessive risk taking, as evidenced by the 30:1 leverage ratio of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

- Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. This where the title of Taleb’s The Black Swan comes from. Europeans used to think all swans were white. Then in 1697 two Dutch explorers discovered black swans in Australia. Only seeing white swans didn’t mean all swans were white. Another example: a turkey will mistake being well fed all year for evidence of a great life, only to be surprised a few weeks before Thanksgiving. Asking “what’s the next black swan event?” ignores their main feature: black swans are not predictable.

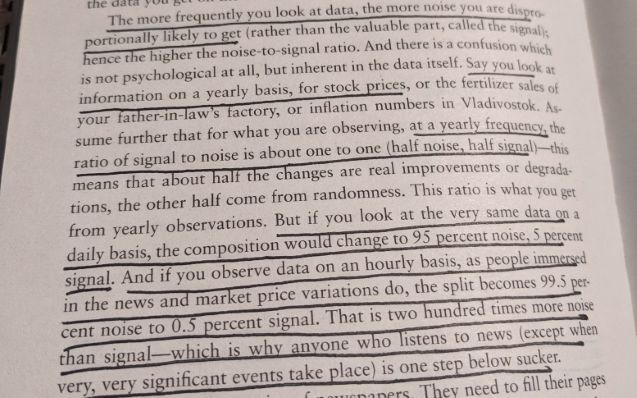

- The more data you have, the less you know what’s going on. Around the clock market access and massive amounts of data translate to unlimited behavioral pitfalls for investors. The more frequently you look at data, the more noise you are likely to see.

- Don’t let the “historical worst case” lull you into a false sense of confidence. An investment’s historical worst loss once didn’t exist (and likely will be eclipsed in the future). This is relevant for investors in 2019 as 10-year return data now only includes the expansion since 2009. Investors should remember that stock markets have experienced 30+ year periods of negative inflation-adjusted returns.

- The possibility of total investment ruin must be minimized. Portfolio survival is a necessity, not an option. Centuries of underwriting profits at Lloyd’s of London were wiped out by asbestos claims. Long-Term Capital Management compounded at 30% per year from 1994 to 1997 and then blew up in a few months. Warren Buffett said: “Charlie and I believe in operating with many redundant layers of liquidity, and we avoid any sort of obligation that could drain our cash in a material way. That reduces our returns in 99 years out of 100. But we will survive in the 100th while many others fail. And we will sleep well in all 100.”

- Don’t mistake the source of necessary knowledge. Taleb calls this the “green lumber fallacy” because a successful lumber trader had no idea why the commodity was called green lumber. Financial media updates you with hundreds of data points: 3M beat earnings estimates, Vietnam’s GDP was higher than expected, and guru ABC thinks a big move is coming in stock XYZ. Remember, these updates are designed to get you to click or watch to increase their ad revenue – not because the information leads to better investing decisions.

Five extra takeaways that aren’t major points but still useful:

- “Much of what other people know isn’t worth knowing.” Taleb talks about reading more old books than new books. If a book’s been in print for 200 years it likely contains some timeless wisdom, compared to whatever is currently at the top of bestseller list.

- Avoid the social treadmill. Start working -> make money -> move to nicer neighborhood -> feel (relatively) poor again. I used to drive a fast car. I now drive a slow Civic. It felt stupid to drive a BMW to the Honda dealership, but it feels smart to save more and spend less.

- Subtractive knowledge is robust, additive knowledge is fragile. Knowing what not to do is powerful. Steve Jobs said: “People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully.” Not smoking and not eating a ton of sugar are subtractive (and cheap) compared to additive and expensive health choices like supplements or the latest diet craze.

- “Ask them what they have in their portfolio.” Taleb cuts through the bullshit and wants investors to state what they own. People might read my posts and think “OK, but how are you invested?” I’m transparent with my strategy and publicly share the models I use.

- Sometimes doing nothing is the right thing. Maybe letting the back heal (rather than having surgery) is the right thing to do, and maybe leaving your portfolio alone (rather than acting on an impulse feeling) is the best move. Unfortunately, some doctors and investment managers are incentivized to do something rather than nothing.

Here’s a link to the book’s Amazon page where there are used copies for $7.